BakeryBiz, Sept-Oct, 2018

From Parsi brune bread to panipuri to the city’s best sourdough, a walk around Mumbai’s old bakeries and restaurants reveals many stories.

Mumbai is a city of bread. From the old-world bakeries to the community khanawal (small local eateries) serving a variety of traditional unleavened breads to artisanal restaurants and hipster cafes offering everything from aged sourdoughs to gluten-free alternative flour confections. The breads chart the history of the many migrations into Mumbai and, despite the many challenges thrown up by the high levels of humidity, are enduring symbols of the city’s culinary diversity. Lounge went on a walk around South Mumbai with Saee Koranne-Khandekar, baker and author of the book Crumbs! Bread Stories And Recipes For The Indian Kitchen, taking a storied and insightful look at the myriad ways in which we break bread.

The morning begins at Girgaon’s crowded Thakurdwar neighbourhood, with its narrow gullies and the constant dishevelment caused by the Mumbai Metro Rail 3 project. Behind the blue construction barriers and next to a street florist is the unassuming façade of Sujata Upahar Griha (formerly known as B Tambe), a Maharashtrian eatery of unspecified date, though patrons and waiters claim it has been around for nearly a century. A true khanawal, Sujata caters to all income brackets, a fact that is quite apparent when we walk in and everyone is welcome, whether a worker from a nearby construction site looking for a glass of water or shop owners and office-goers from the neighbourhood. The menu has definitely not adjusted its prices according to the inflation of our times and till date, the most expensive thing there is a rabdipuri, at `145.

Started by one of the members of the family behind the legendary Tambe Arogya Bhawan in Dadar West, Sujata is our first stop because of its bhakhris. Unlike the standard tandlachi (rice flour) bhakri, which is found in Konkani and Maharashtrian restaurants across the city, at Sujata, the bhakris come in options of jowar, bajra, nachni (finger millet) as well as tandlachi and are served with an assortment of gram flour and horse gram gravies and a side serving of sliced onions, a wedge of lime, fried green chillies and a dry chutney. The latter, along with the bhakris, forms an entire meal for farmers in rural Maharashtra. “The thing about a bhakhri is that it takes much longer to cook than a roti and therefore not all commercial establishments are willing to invest in it,” says Khandekar.

Our freshly made jowar bhakhri, when it arrives, even though not puffed up, is well-cooked, with a sweetness that comes from the freshly milled flour. Its accompanying kulith pithi (milled horse gram gravy) is smooth, mildly spiced and topped with freshly grated coconut and coriander. When I ask her about the bhakri’s thickness, which is more than that of your average roti, Khandekar shares an interesting anecdote. “There are places in Maharashtra that pride themselves on the really thin bhakhris. For example, my grandmother came from coastal Maharashtra, where girls used to be judged on their skill of how thin they rolled their bhakhris. Then she got married to my grandfather, who came from an area where the bhakris were eaten thick. So there was a constant war in my house,” she says. However, our bhakhri is definitely agreeable for a novice like me and even passes under Khandekar’s critical palate.

“There are places in Maharashtra that pride themselves on the really thin bhakhris. For example, my grandmother came from coastal Maharashtra, where girls used to be judged on their skill of how thin they rolled their bhakhris.” Saee Koranne-Khandekar

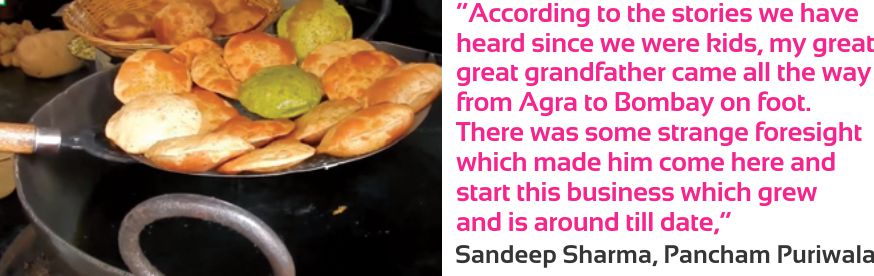

A quick cab ride or a brisk half-hour walk leads to the next stop on the trail—Pancham Puriwala, reportedly one of the oldest eateries in all of Mumbai, located at the head of the bustling Borabazar area opposite the grand Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. Its current owner, Sandeep Sharma, one of the three brothers who manages the eatery, juggles the bills and repeats the oft-told legend of how the place started. “According to the stories we have heard since we were kids, my great great grandfather came all the way from Agra to Bombay on foot. There was some strange foresight which made him come here instead of Calcutta, which was the hub back then, and start this business which grew and is around till date,” he says. Back then the establishment was quite basic; however, there must have been something about the simple, crisp puris and bhaji dished out by this enterprising migrant that made them a hit in the area and the business endured, passing on from one generation to the next. “Even though we have increased our menu a little bit, the backbone is still the same. The original dish that we were known for was puri with aloo and bhopla bhaji (potato and pumpkin curry). The reason pumpkin was mixed in was because it made the potato easier to digest,” says Sharma. The place has undergone a few updates but is still low key, drawing a cross section of people. Just like Sujata, the prices are extremely controlled. “From a rich man to a beggar, anyone can eat here,” says Sharma. Our meal is one of the most elaborate on the menu and is called the Pancham Thali, with various seasonal veggies, dal, raita and of course the star attraction, five assorted puris in plain, masala, beetroot, spinach and paneer variants. It is the most expensive thing on the menu, at `150.

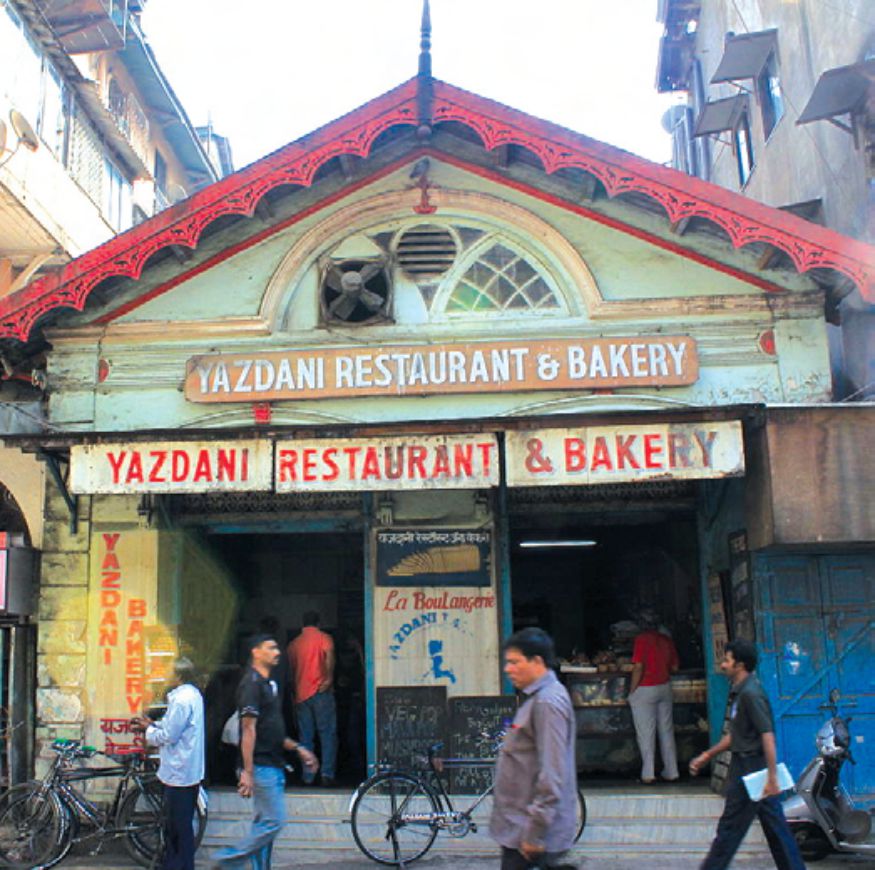

Picking our way through the cramped streets of Borabazar towards Yazdani Bakery, Khandekar points out the lanes leading off the main market where, as a child, she would come shopping with her grandmother for vegetables. “Vendors from Vasai would come in with fresh local produce of the kind that wasn’t available at the local grocer and would include the exotics like banana blossom,” she says. As the narrow gullies of the market give way to the by-lanes leading off the corporate corridors of Mumbai’s Fort area, Yazdani suddenly pops up like a vision whisked out of another era.

“Persian-style Irani bakeries came to India somewhere around the 19th century and thrived alongside Gujarati trade houses and shops, occupying the corner spots of buildings that were shunned by Hindus, who considered them inauspicious. These bakeries were among the first to prepare freshly baked leavened bread and other foods bearing colonial influences,” writes Khandekar in Crumbs. The building, which was once a Japanese bank, remains quite untouched by the 21st century, with a high-beamed ceiling, a traditional loaf-cutting machine and a wood-fired oven which has been burning for the last 100 years. A blackboard on the wall holds the entire menu, which includes a grand total of nine items: brun maska, bun maska, egg puff, mava puff, veg puff, carrot cake, mava cake, bread pudding and fiery ginger biscuits. And of course there is lots of sweet Irani tea in kadak and regular options. Our order is simple: a portion of brun maska, a hard and crusty bun slathered generously with Amul butter, a plate of pillowy-soft raison-studded buns with butter and many cups of strong sweet tea. Tirandaz, the man behind the counter, is the third-generation owner who keeps urging us to go about photographing the place with haste before his uncle, who “might not take as kindly to it”, arrives. “The oven is almost their sacred space which they are very guarded about and they will not let you get too close or touch anything,” says Khandekar. With the mythical oven, walls adorned with old family photographs and newspaper cuttings, a grandfather clock keeping the hours and the sweet smell of bread wafting around, this is much more than just another bakery.

The journey from Yazdani to The Table takes about 15 minutes on foot, but it feels like time-travelling through an entire century. One of South Mumbai’s favourite fine dining establishments, known for pushing the boundaries of how the city looks at food by using high-quality fresh, local and seasonal produce to create an innovative menu, The Table is also a front-runner in the sourdough game. Originally baking out of The Table’ s kitchens, the bread production has shifted entirely to Magazine Street Kitchen, an experimental kitchen-lab and dining space. In Byculla while The Table has an assortment of breads for all uses, from buttery cuboid brioches, baguettes, burger buns to ciabattas and focaccias, its bakery also supplies to leading restaurants across town for different applications by different chefs. However, it is the sourdough, baked in a brick oven, that is the star and is reserved for The Table alone. Chef Divesh Aswani, the head chef at The Table and Magazine Street Kitchen, brings out two loaves, an amber-coloured round loaf and the other with a high percentage of starter and a near-charcoal crust. “The sourdough culture is very big in San Francisco and this dark loaf was popularized by the Tartine bakery there. And although to some this might look burnt, what it actually is, is a beautiful caramelized crust,” says Khandekar. As Aswani and Khandekar go deep into nerdy conversations about sourdough temperatures, humidity and the chemistry of starters, it is difficult to ignore the singular beauty of the bread. The starter that gives it both flavour and sheen is about six years old and is fed and nurtured on a regular basis, its flavours fermenting and maturing with time. “It is darker than normal bread and chewier and does have a sour flavour and these nuances are not easy for everyone to get as it’s not as sweet as the standard commercial loaves,” says Aswani. As the base of their avocado toast, open sandwiches, it is a hit, with the right amount of crunch and texture. And while the sourdough revolution is slowly rising across Mumbai, The Table’s dark sourdough is one of the best the city has to offer.

The last stop on Khandekar’s bread trail is Theobroma, a Mumbai institution and what some would consider a veritable church of confectionary, known all over the country for its dense brownies. The iconic Colaba outlet, with its pastel pink and teal signage is alive with customers streaming in and out for a quick sandwich, a last-minute birthday cake, an after-lunch brownie or a bread haul. In her book, Khandekar describes this 18-year-old family run bakery as a place which started off with the idea of introducing “good unadulterated bread to the market, but discovered, soon enough, that an affordable price was integral to acceptance…. It was difficult to explain to the average buyer that a brioche was more expensive because of the sheer quality and quantity of ingredients used in the preparation.” The owner, Kainaz Messman, ploughed ahead, handcrafting and making small batches of breads much before “artisanal” became a fashionable culinary term. She worked with sourdough and adapted her breads to the local context, coming up with interesting variations like the Parsi chutney bread and the kokum baguette. “The Parsi chutney has coconut, coriander and chillies but what gives it an unusual sweetish-sour flavour is the sugarcane vinegar. And Kainaz had this brainwave and decided to swirl this chutney through her dough and since then it’s been quite a favourite,” says Khandekar. It’s like a ready-made chutney sandwich and all it needs is a smattering of butter. Similarly a baguette studded with tiny pieces of kokum is a surprising and deliciously local adaptation of the more conventional olive baguette. These apart, Theo’s does a range of loaves, from high-fibre and whole wheat to gluten-free options.

Even in this tiny spot of South Mumbai, this diversity among breads is a window to the city’s equally heterogenous culture. This self-guided bread trail is best traversed over a couple of hours, interspersed with some brisk walking, a beer or two at Woodside Inn, a spot of shopping on the Colaba Causeway. End with a coffee at the Sea Lounge at Taj Mahal Palace Hotel while watching the sun set at Gateway of India.