BakeryBiz, May-Jun, 2018

Want a pet? Ideally something less annoying than a Tamagotchi. Try sourdough. It’s unpredictable, comforting and will keep you up at night, as you feed it and wait for it to breed — so to speak. Prabalika M. Borah takes a peep into sourdough.

Unfortunately, Sourdough Hotel’s clients don’t have access to TripAdvisor. So we’ll never really know what they thought about the food, water or massages. Nevertheless, they thrive. So if you need boarding for your bread, head to Stockholm. For 300 Swedish krona a week (roughly ₹2,300), this hotel set in the city’s hip SoFo district keeps sourdough thriving while owners go on holiday — because heaven forbid it dies of neglect while you sun yourself in Ibiza.

Rolling your eyes? Well, hold on to your toast: this is just the beginning. Home cooks, food nerds and artisan bread-makers are switching loyalties: brown bread is too pedestrian, muffins too predictable and brioche too pretentious. If you’re looking for bread with personality, sourdough is the way to go.

Consisting of flour, water and live micro-organisms, this fermented bread is made the old-fashioned way, without any help from commercial yeast. Which could explain why, in an age that values provenance, tradition and technique, this style of bread is making a comeback. Loyalists vouch for its taste and overall goodness, stating that once you taste sourdough you cannot eat other breads. Either way, it’s time you learn about it, if you don’t intend to get elbow-deep in flour, for sourdough is the reigning topic at every trendy baker’s table today.

Genesis

The bread dates back to ancient Egypt, if scriptures and cave paintings are to be believed. The technique lost steam and almost dropped off the radar in the Middle Ages, only to be revived in the early 1800s. With the invention of commercial yeast, sourdough almost became obsolete.

Author of Theory of Bakery and Patisserie and a chef specialising in Indian cuisine, Parvinder S Bali, connects bread-making with the cultivation of wheat. “The origins of the first bread are unknown, but wheat has been cultivated for more than 5,000 years. Leavening of the bread must have been purely accidental, as the previous day’s dough would have been left over. The wonderful fermented smell would have urged the baker to bake it. Khameeri roti is a good example.”

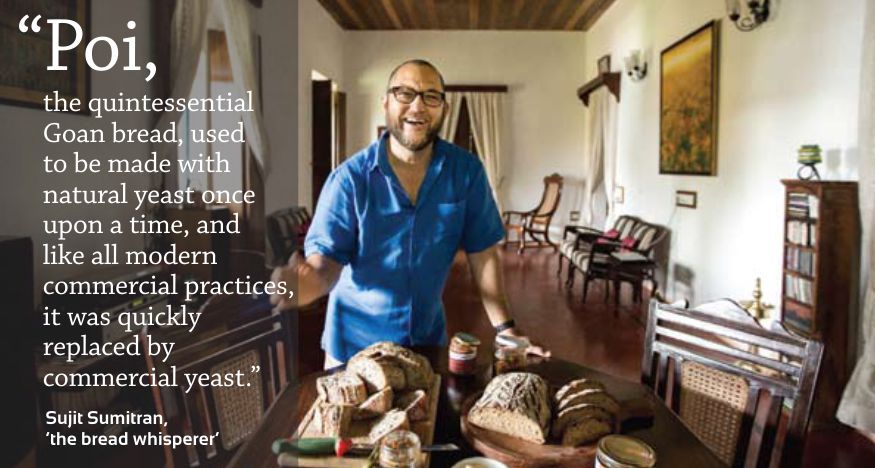

Sujit Sumitran, popularly known as ‘the bread whisperer’, is a name synonymous with sourdough in India. Based in Goa, where he spends hours every week baking artisanal bread, he also travels across the country to conduct workshops. He says, “Poi, the quintessential Goan bread, used to be made with natural yeast once upon a time, and like all modern commercial practices, it was quickly replaced by commercial yeast. Based on what I’ve heard from old-timers, the pois of today — and I’ve eaten many — are just a shade of what they really should be. For starters, they’re quick-rise breads, and in most cases, the dough is pure refined flour with just a different shape and some bran dusted on.”

“I think there is a global renaissance of sorts happening on the artisanal front, a move away from soul-less, mass-produced products,” comments Sumitran. “This, to my mind, is largely fuelled by the realisation that speed and convenience come at a price. Consequently, conscious folks are adopting ‘slow’ as a lifestyle change, and food is definitely up there on their radar.

So what are the magic ingredients? “To make your own sourdough bread you need a starter,” says Arundati Rao, Hyderabadbased home baker, popular for her baking classes.

The art

“A starter is nothing but a blend of water and flour left to ferment in room temperature for a couple of days. This requires daily care by way of feeding with flour and water. Bacteria keeps growing in the dough and it acts like yeast. A portion of starter dough can be used to make a new loaf of bread. Maintaining the shelf life of your sourdough is pretty much a food science and an art; it varies around the world due to climatic conditions.” Rao further breaks it down like a simple science class, “When flour and water are left to ferment, it supports wild yeast and lactobacilli which is easily available in the atmosphere. On being fed properly and kept alive, it acts as yeast, which makes baking possible without factory-made dry yeast.”

The fact that this bread is healthier than conventional bread is not the only reason it’s getting so popular. This renaissance has much to do with social media, especially Instagram.

Wild yeast can be fussy and finicky: it needs cooler temperatures, acidic environments, and works much more slowly. Then why not opt for something easier? “There is a lot of data available these days that indicate that many of the modern lifestyle diseases are food and wellness induced,” says Sumitran. He adds, “Fermented food has been around in India for thousands of years, and sourdough bread is just one manifestation of it. What is available as bread today, mostly works on the paradigm of more output (volume) with less time, while sourdough is about more output (wellness) with enough time.”

******************************************************************************************************************************************************

Pathare Prabhu Pav

As I foraged the Internet for an Indian counterpart of sourdough, I found Bijay Thapa, a Delhi-based wedding cake maker and baker. Thapa brought up his days as a Masterchef India participant. “I bemoaned the lack of baking culture in India to my friend Kalpana Talpade. She surprised me with the details of the Pathare Prabhu community, that started a yeast culture using milk, channa dal and potatoes. They bake a bread with it called parvipav or patharepav. From her description, I could say the home-grown pav has to be the Indian answer to the English sourdough,” he says.

Parvipav is fluffy and soft, with a muffin-like texture. It is best relished with spicy mutton curry, and according to KalpanaTalpade, “Vegetarians love to eat it with aamras.” The starter for the pavis made with channa dal, unpeeled potato, milk and water. Talpade says, “I like to heat my milk and water together for optimal fermentation. On a warm day fermentation should happen within 12 to 15 hours. The fermented liquid is used to leaven the bread batter and made into parvipav. Weather and climate play a big role in the process.”

The community migrated from Rajasthan and Gujarat many years ago, settling in Mumbai. “It helped them mingle with the British and be influenced by their food habits. This could explain the strong baking culture.”

Recipe for Pathare Prabhu Pav (Gonda in Marathi)

You will need one steel tumbler with a narrow opening and a bigger steel vessel with lid.

Ingredients

- 2 fistfuls of chana dal, not washed or soaked

- 1 potato, washed and cut into pieces with peel left on.

- 1/3 spoon of eating soda

- One cup of milk

- One cup of water

Method:

Mix water and milk and bring it to a boil. Put the diced potato and chana dal in the tumbler and pour the hot milk and water into the mixture. Close the tumbler with a steel cover or vessel make it air-tight.

Then, place the tumbler with the contents onto another bigger vessel and close the lid. Then place it in a warm and secluded place. Avoid opening it to check, leaving it undisturbed. It takes over night for the yeast to form. After keeping it aside for 12 to 14 hours, the next day a froth will form on the mouth of the smaller vessel. Use the froth, water and milk contents to knead your dough for the bread.

Note: Strain off the chana dal and potato pieces.

This recipe is ideal to make pathareprabhupav, but with 3 cups of flour.

*****************************************************************************************************************************************************