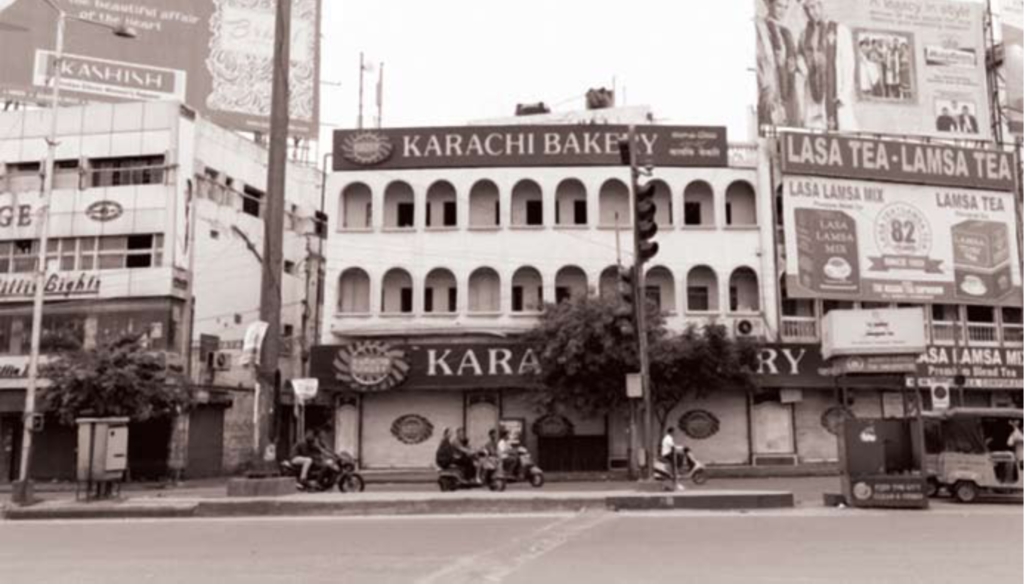

As the Bengaluru outlet of Hyderabad’s Karachi Bakery is attacked in the wake of the terrorist suicide bombing of Indian paramilitary forces in Pulwama, Mallik Thatipalli takes a look at the history and success story of his neighbourhood bakery.

I grew up two streets away from Hyderabad’s iconic Karachi Bakery, in the 1990s there was only one branch, its flagship outlet at the historic Moazzam Jahi Market crossroads and Karachi was our go-to place for breads, biscuits and buns. Karachi was the major landmark for our locality and ‘bet’ matches in cricket were settled by a slice of its delicious dilkush for years. It was impossible to pass 200 meters within their kitchens and not get allured by the delicious aromas wafting from the ovens.

Their fruit bread used to sell out by 4 pm and there was no equal for its most famous product, the fruit biscuit, which was the only souvenir cousins and family in other cities wanted from us. So much so that every Hyderabadi knows that there is fruit biscuit and then there is Karachi fruit biscuit. A popular common joke locally regarding the bakery was that it was ‘world famous’ in Hyderabad.

Till the early 2000’s Karachi remained a local institution, though a venerable one at that. But then Hyderabad was littered with old and popular bakeries like Subhan Bakery and Niloufer. While all of them still remain popular in their local niches, none of them have seen a success story akin to Karachi.

Every Indian city has its fair share of iconic bakeries – from Mumbai’s Yazdani Bakery to Wenger’s in Delhi and Albert in Bengaluru, these local institutions are rich on nostalgia and have become a part of their city’s folklore thanks to a combination of their long innings, strong recall value and instant connect with people. Hyderabad has a similar relationship with its bakeries, and Karachi finds itself ranked right at the top.

‘Sandhya Balakrishna, the author of the book The Bakeries of Hyderabad’.

Sandhya Balakrishna, the author of the book The Bakeries of Hyderabad, puts Karachi’s phenomenal growth from another small Hyderabad bakery to a nationwide behemoth to their ability to think ahead and invest in some brilliant branding. “I think they took the right risks at the right time,” she says. “They realised the power of branding, were quick to understand that having more branches leads to more visibility and had a fabulous marketing strategy in place which capitalised on their unique strength in baking.”

Indeed, from one store in 2000 to 23 in Hyderabad currently and branches in Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai amongst other cities, it is a triumph of indigenous business which was built along the way. While some attribute it to their instinctive Sindhi entrepreneurial flair, others think that its ability to plan ahead paid rich dividends. One illustration of their business acumen was when they started their counter at the Hyderabad airport paying a staggering amount of rent but persisted because it gave them visibility amongst travelers to other cities, thus laying the groundwork to expand out of Hyderabad.

The genesis

Started in 1953 by Khanchand Ramnani who migrated to Hyderabad with his sons Hassram and Narayanda, the family was merchants by profession and originally belonged to Sindh in Pakistan. What enabled their instant success were their fruit biscuits which quickly became best sellers cementing the bakery’s path to success. It was on the back on this one product that a whole empire was built.

Their fruit biscuit is an unassuming square shaped variety dotted with green and red pieces of papaya jelly which became a part of Hyderabad’s identity ever since it was launched. Biscuits are a big hit here (thanks to the culture of drinking tea at Irani cafes) and Karachi monopolised a segment of the market by the early 60s.

A closely guarded family recipe ensured the unique quality of fruit biscuits were never replicated by rivals and soon they began to stock other quintessential Hyderabadi bakery products — dilkush, Osmania biscuits and rusks to cater to their growing clientele.

Always ahead of the curve, they started introducing oatmeal, ragi and sugar-free sweets in the early 2000’s ensuring that while their traditional clientele was kept happy, they added new customers and branches, usually youngsters from other cities, who came into Hyderabad, thanks to the IT boom.

What aided their growth, Balakrishna feels, is their focus on quality. She says, “You never say get biscuits from a bakery, you say get them from Karachi bakery. Therein lays the secret of their success. Also, during the course of writing my book, I was surprised that that Lekhraj Ramnani, one of the owners, personally mixes the ingredients each day at their factories.” She adds that one look inside any Karachi outlet shows that people know exactly what they want.

While their pink, blue and white montage remains a Hyderabad icon, Manoj Ramnani of Karachi Bakery says that quality and affordability have been the cornerstones of their success. He says, “Our biscuits stay fresh for three months, thanks to the ingredients and packing while our USP is the wide range we offer.”

Name game

As reports of the store asked to cover up their name emerge from Ahmedabad and Bengaluruin the wake of the terror attack in Pulwama, most Hyderabadis are bemused by the turn of events for the bakery and its name have been a part and parcel of the city’s landscape for over six decades now.

With the company putting out a note reasserting their Indian origins, Ramnani is unfazed by the controversy and says, “While there have been sporadic events in two outlets, by and large, people have been supportive. You scroll through social media and most of the comments have been encouraging.” He points to the crowded MJ Market branch and remarks that there has been no fall in footfalls over the past few days.

The attack has been met with derision by most users on social media and the sentiment runs strong in Hyderabad, that a successful homegrown brand is at the receiving end of hostility on flimsy grounds. While one needs to wait and watch how the events unfold over the next couple of days, Ramnani says that he is confident that this would blow over soon enough and adds, “Karachi biscuits are as Hyderabadi as biryani and haleem. No one can doubt that.” (COURTESY: FIRSTPOST)

Lekhraj Ramnani

“You never say get biscuits from a bakery, you say get them from Karachi bakery. Therein lays the secret of their success. Also, during the course of writing my book, I was surprised that Lekhraj Ramnani, one of the owners, personally mixes the ingredients each day at their factories.”

Karachi Bakery covers signboard after protests

A Karachi Bakery outlet in Bengaluru was forced to cover up the word “Karachi” in its signboard after a mob of 20-25 people protested against the reference to the city in Pakistan, from which it takes its name. The mob assembled near the bakery’s outlet in Indiranagar, demanding that its name be changed. The development comes a week after the deadly Pulwama attack in Kashmir, where more than 40 CRPF personnel were killed in a suicide attack. A cine workers association has banned all artists from Pakistan, while the BCCI has sought to sever sporting ties with the country.

The mob refused to disperse from the bakery and continued to protest. To placate the crowd, the establishment covered up the word “Karachi” in its signboard and put up an Indian flag. There was no property damage or violence at the site. The branch’s manager told a section of the media that men who were part of the mob claimed to “know people in the army.”

“They thought we are from Pakistan. But we have been using this name for the last 53 years. The owners are Hindus; only the name is Karachi bakery. To satisfy them, we put up the Indian flag,” the manager said.

The Karachi Bakery was started in Hyderabad in 1953 by Khanchand Ramnani, who migrated from Karachi during the Partition. It has since grown into a nationwide franchise. Despite the protest, the bakery continued to operate till its scheduled closing time of 11 pm.