Bread was introduced to India by the Portuguese. Rathina Sankari traces the varieties of Goan bread and checks how they are connected with breads in other places where Portugal had historical influence.

It is rush hour at Cafe Corner in Mapusa, a town in North Goa District, India, and the locals are queueing up for breakfast. On each table is a plate of curry made of red beans, potatoes or white peas, paired with different varieties of Goan leavened bread.

In addition to rice, bread is a daily source of carbohydrates for Goans. Varieties include pav, a rectangular, pull-apart refined flour bread, the pita-like poi, katro pav (butterfly bread), and kakon, which resembles a bagel.

I never knew about these Goan breads until recently. Having lived my life in Pune, a city more than 400km away from Mapusa, I only knew of pav, which we stuffed with a deep-fried mashed potato patty coated with chickpea batter.

Imagine my surprise when I learned that the Portuguese introduced oven-baked bread to India. It happened centuries ago, when they were in search of a sea route to India. Navigator and explorer Vasco da Gama was the first European to reach India by sea in 1498, landing in Calicut in Kerala. In 1510, Goa became one of the Portuguese holdings in India and was later the capital of the Portuguese Estado da India (State of India).

In her book Curry: a Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, Lizzie Collingham details the strong Portuguese influence on Indian cuisine. They introduced vinegar marinades, chillies, potatoes, tomatoes, pineapples, cashews, fennel and guavas.

They also missed their bread from back home, which was essential for religious purposes such as communion.

Wheat was available in India, but yeast – a vital ingredient for making leavened bread – was unheard of in the land. So the Europeans used toddy – a local alcoholic drink made from the sap of the palm tree – to prove the dough.

They passed on these culinary skills to the Indian women they married, who soon became expert bakers. Goan historian Dr Fatima da Silva Gracias writes in her book Cozinha de Goa: History and Tradition of Goan Food that the Portuguese Jesuits taught bread baking to locals in the villages of Salcete in South Goa in the 16th century. Today Indians in Western India, primarily the states of Maharashtra, Goa and Gujarat, enjoy Portuguese-Goan bread as a staple food.

The Goans love to have their bread with tea or with local dishes such as vindaloo (a derivative of Portuguese vinha d’alhos), xacutti (a Goan curry), eggs and bacalhau (salted cod). The daily bread market in Mapusa is open in the early morning and late afternoon. Every village in Goa has its own baker.

The term pav, which is widely used in India, derives from the Portuguese pao, a generic word for bread. Poder – Goan for baker – has its origins in the Portuguese padeiro.

I visited Portugal to find out more about the original breads. I noticed cotton bags with drawstrings placed on restaurant tables. The saco de pao (bread bag) is used to store bread to retain its freshness and ensure it doesn’t go mouldy. My driver, Miguel Sa, says that at his home in Sao Brissos, Alentejo, he hangs his bread bag at the gate, and the padeiro puts the bread in there when he makes a delivery.

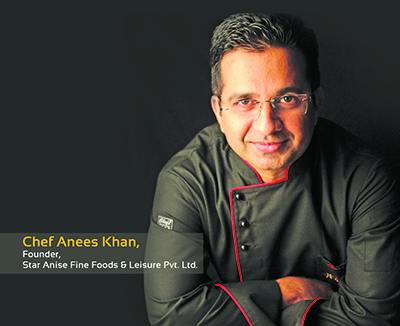

Each region in Portugal has its local variation, such as the pao de mafra from around Lisbon, the dark bread made of corn and rye – broa de Avintes – in the north, the crusty wheat based pao alentejano in the south, and the dense rye bread, Tras-os-Montes from the northeast. Bread in Portugal is made from many grains and cereals including corn, rye and wheat.

It is not just relished as an accompaniment but finds prominence in dishes like acorda, gazpacho and desserts.

David Wong, food educator with the Institute of Tourism Studies, Macau, says: “The Chinese bao was consumed before the Portuguese arrived in the [16th century]. But that didn’t limit the palate of the Macanese.

The Portuguese breads, pao alentejano and the Tras-os-Montes, are quite popular in Macau, which was once an overseas Portuguese territory.”

Sure enough, at A Lorcha, a restaurant in Macau, the menu offers traditional Portuguese dishes that include pao, bacalhau, olives, seafood rice, pork dishes and port. Macanese pork-chopstuffed Portuguese bread rolls, or papo secos, are a must-try for visitors.

Wong points out that Portuguese breads are also found in other old Portuguese colonies including Brazil, its former African possessions – Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Sao Tome and Principe – and the island of Timor.

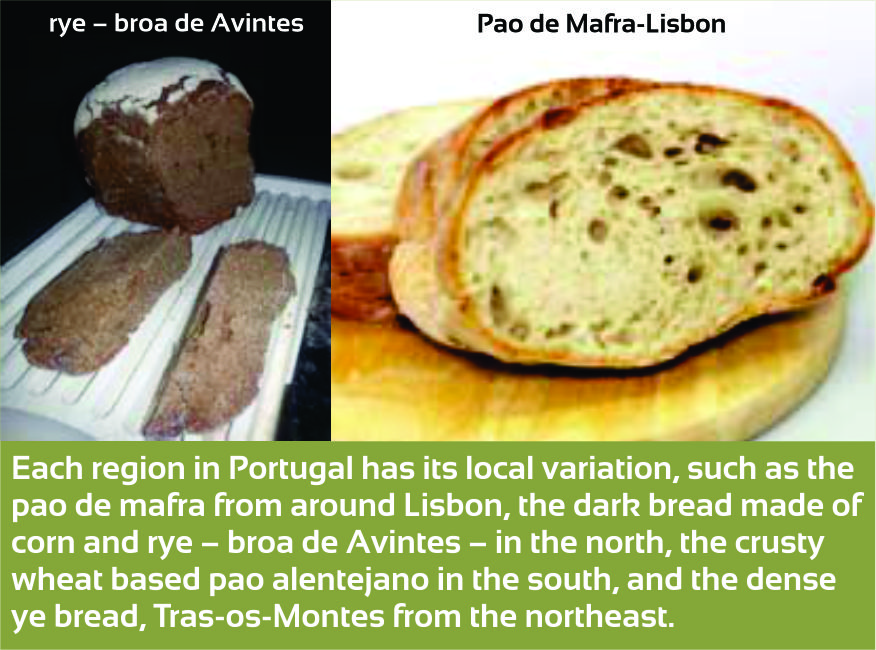

Back in Portugal, at the Gleba Bakery in Lisbon, I find the talented, young Diogo Amorim covered with flour. He is baking batches of dense pao de centeio (rye bread), broa de milho and pao de trigo (a wheat bread).

A passionate baker who specialised in gastronomical sciences and is a staunch believer in traditional baking methods, he uses local produce and ferments the bread using natural lactobacilli.

The sourdough breads in his kitchen are baked to perfection without using industrial yeast and hence last longer, and are easily digestible. He gives me a quick lesson on the science of sourdough and Portuguese bread.

As the loaves are pulled out of the oven he smells, taps and feels them. He then cuts one and offers me a piece of the light and warm pao de trigo. I take a bite. It’s perfect, just the kind of thing you would want to mop up some vindaloo back in Goa.